Advertisement

Electoral college explained: how Biden faces an uphill battle in the US election

Trump won the presidency in 2016 despite Clinton receiving almost 3m more votes, all because of the electoral college. How does the system work?

Who elects the US president?

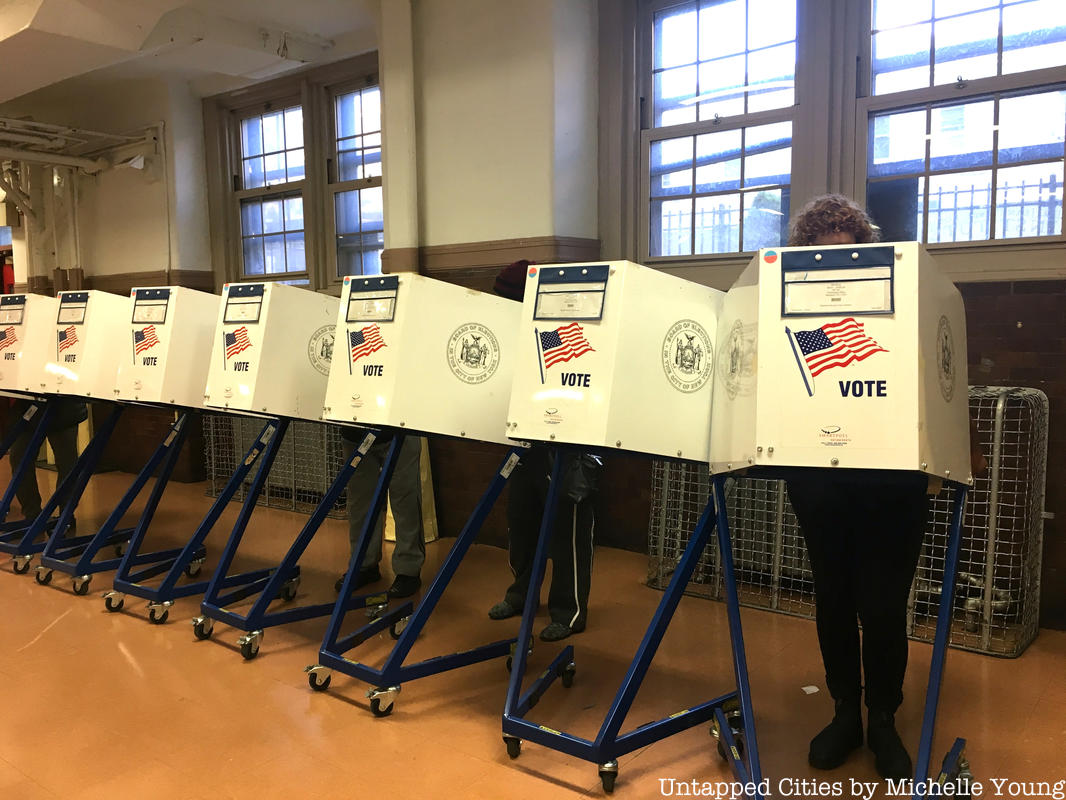

When Americans cast their ballots for the US president, they are actually voting for a representative of that candidate’s party known as an elector. There are 538 electors who then vote for the president on behalf of the people in their state.

Each state is assigned a certain number of these electoral votes, based on the number of congressional districts they have, plus two additional votes representing the state’s Senate seats. Washington DC is also assigned three electoral votes, despite having no voting representation in Congress. A majority of 270 of these votes is needed to win the presidency.

The process of nominating electors varies by state and by party, but is generally done one of two ways. Ahead of the election, political parties either choose electors at their national conventions, or they are voted for by the party’s central committee.

The electoral college nearly always operates with a winner-takes-all system, in which the candidate with the highest number of votes in a state claims all of that state’s electoral votes. For example, in 2016, Trump beat Clinton in Florida by a margin of just 2.2%, but that meant he claimed all 29 of Florida’s crucial electoral votes.

Such small margins in a handful of key swing states meant that, regardless of Clinton’s national vote lead, Trump was able to clinch victory in several swing states and therefore win more electoral college votes.

Biden could face the same hurdle in November, meaning he will need to focus his attention on a handful of battleground states to win the presidency.

The unequal distribution of electoral votes

While the number of electoral votes a state is assigned somewhat reflects its population, the minimum of three votes per state means that the relative value of electoral votes varies across America.

The least populous states like North and South Dakota and the smaller states of New England are overrepresented because of the required minimum of three electoral votes. Meanwhile, the states with the most people – California, Texas and Florida – are underrepresented in the electoral college.

Wyoming has one electoral college vote for every 193,000 people, compared with California’s rate of one electoral vote per 718,000 people. This means that each electoral vote in California represents over three times as many people as one in Wyoming. These disparities are repeated across the country.

Who does it favour?

Experts have warned that, after returning two presidents that got fewer votes than their opponents since 2000, the electoral college is flawed.

In 2000, Al Gore won over half a million more votes than Bush, yet Bush became president after winning Florida by just 537 votes.

Professor George Edwards III, at Texas A&M University, said: “The electoral college violates the core tenet of democracy, that all votes count equally and allows the candidate finishing second to win the election. Why hold an election if we do not care who received the most votes?

“At the moment, the electoral college favours Republicans because of the way Republican votes are distributed across the country. They are more likely to occur in states that are closely divided between the parties.”

Under the winner-takes-all system, the margin of victory in a state becomes irrelevant. In 2016, Clinton’s substantial margins in states such as California and New York failed to earn her enough electoral votes, while close races in the battleground states of Pennsylvania and Michigan took Trump over the 270 majority.

As candidates easily win the electoral votes of their solid states, the election plays out in a handful of key battlegrounds. In 2016, Trump won six such states - Florida, Iowa, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin – adding 99 electoral votes to his total.

The demographics of these states differ from the national average. They are older, have more white voters without college degrees, and often have smaller non-white populations. These characteristics generally favour Republicans, and made up the base of Trump’s votes in 2016.

For example, 67% of non-college-educated white people voted for Trump in 2016. In all six swing states, this demographic is overrepresented by at least six percentage points more than the national average.

Trump's core demographics are over-represented in swing states

Guardian graphic. Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2014-2018 American community survey five-year estimates

The alternatives

Several alternative systems for electing the president have been proposed and grown in favour, as many seek to change or abolish the electoral college.

Two states – Maine and Nebraska – already use a different method of assigning their electoral college votes. The two “Senate” votes go to the state-wide popular vote winner, but the remaining district votes are awarded to the winner of that district. However, implementing this congressional district method across the country could result in greater bias than the current system. The popular vote winner could still lose the election, and the distribution of voters would still strongly favour Republicans.

The National Popular Vote Compact (NPVC) is another option, in which each state would award all of its electoral college votes in line with the national popular vote. If enough states signed up to this agreement to reach the 270 majority, the candidate who gained the most votes nationwide would always win the presidency.

However, the NPVC has more practical issues. Professor Norman Williams, from Willamette University, questioned how a nationwide recount would be carried out under the NPVC, and said that partisanship highlighted its major flaws. Only Democratic states are currently signed up, but support could simply switch in the future if a Republican candidate faces winning the popular vote but not the presidency.

The NPVC is a solution that would elect the president with the most votes without the difficulty of abolishing the electoral college that is enshrined in the constitution.

In 1787, the Founding Fathers could not decide on the best system to elect the president. Some delegates opposed a straight nomination by Congress, while others wanted to limit the influence of a potentially uninformed public and the power a populist candidate could have with a direct popular vote. The resulting electoral college, with electors acting as intermediaries for their states, is their compromise.

This system also invoked a clause known as the three-fifths compromise between northern and southern delegates, as they debated how slavery would affect a state’s representation. Their agreement was that three-fifths of enslaved individuals (who could not vote) would count towards a state’s population, awarding a disproportionate amount of power in the electoral college to the southern states.

While the 13th amendment which abolished slavery in effect removed the three-fifths clause, the impacts of an unbalanced electoral college with unequal representation remain.

The current system is still vulnerable to distorted outcomes through actions such as gerrymandering. This practice involves precisely redrawing the borders of districts to concentrate support in favour of a party. The result being abnormally shaped districts that disenfranchise certain groups of voters.

Today, an amendment that would replace the college with a direct national popular vote is seen by many as the fairest electoral system.

According to Professor Edwards III, “There is only one appropriate way to elect the president: add up all the votes and declare the candidate receiving the most votes the winner.”

No comments:

Post a Comment