HISTORICAL

BACKGROUND OF AFRICA'S WORLD WAR AS AT 2017

By Paul

Nantulya

Paul

Nantulya

Paul

Nantulya

Paul

Nantulya

DRC’s political crisis has

galvanized and revived many of the estimated 70 armed groups currently active

in the country, making the nexus between political and sectarian violence by

armed militias a key feature of the DRC’s political instability.

The legitimacy of the government of the Democratic Republic of

the Congo (DRC) in its peripheral regions has always been tenuous. Throughout

the country’s history, the most vehement opposition to Kinshasa has frequently

emerged from its most far-flung provinces, such as Kasai, Katanga, and the

Kivus. Today, this fault line is being exacerbated by President Joseph Kabila’s

decision to suspend elections and remain in office after the end of his

constitutionally mandated term limit in December 2016.

In addition to triggering protests across many cities, the political crisis has revived and galvanized armed groups and militias in areas that harbor long-running grievances against the central government. Some insurgents have openly called on the President to step aside, even as their activities remain local. Others have expanded their attacks outside their traditional areas of operation in an apparent effort to exploit worsening grievances. Still others have focused their attacks on government personnel and facilities, including electoral commission offices, saying that preparations for new elections are meaningless as long as Kabila is a candidate.

In the DRC, the nexus between political and sectarian violence by armed militias is a key feature of political instability. This occurs in a climate of endemic corruption, weak or nonexistent institutions, and lack of trust between citizens and government. Nefarious actors thrive in this environment. This review highlights some of the patterns of violence by the estimated 70 armed groups active in the DRC—as uncertainty and anxiety over Kabila’s intentions intensify.

In addition to triggering protests across many cities, the political crisis has revived and galvanized armed groups and militias in areas that harbor long-running grievances against the central government. Some insurgents have openly called on the President to step aside, even as their activities remain local. Others have expanded their attacks outside their traditional areas of operation in an apparent effort to exploit worsening grievances. Still others have focused their attacks on government personnel and facilities, including electoral commission offices, saying that preparations for new elections are meaningless as long as Kabila is a candidate.

In the DRC, the nexus between political and sectarian violence by armed militias is a key feature of political instability. This occurs in a climate of endemic corruption, weak or nonexistent institutions, and lack of trust between citizens and government. Nefarious actors thrive in this environment. This review highlights some of the patterns of violence by the estimated 70 armed groups active in the DRC—as uncertainty and anxiety over Kabila’s intentions intensify.

Kasai

The south-central region of Kasai (approximately the size of

Germany) is a traditional opposition stronghold and home to the late veteran

opposition leader, Étienne Tshisekedi, popularly known as the “father of

Congolese democracy.” It is also a microcosm of the center-periphery conflicts

that have bedeviled the DRC since independence.

In the absence of central authority, traditional leaders have played a vital role throughout the DRC’s tumultuous history by mediating local disputes, maintaining law and order, and allocating resources, including land. They also perform spiritual functions. Traditional leaders are appointed according to local customs and then recognized by the state. To maintain their authority, they often align themselves to the regime—something that Jean-Pierre Mpandi, who was highly critical of the ruling party, refused to do.

In the absence of central authority, traditional leaders have played a vital role throughout the DRC’s tumultuous history by mediating local disputes, maintaining law and order, and allocating resources, including land. They also perform spiritual functions. Traditional leaders are appointed according to local customs and then recognized by the state. To maintain their authority, they often align themselves to the regime—something that Jean-Pierre Mpandi, who was highly critical of the ruling party, refused to do.

In 2016, the government refused to recognize Mpandi as the

traditionally appointed Kamwina Nsapu—a title given to the hereditary leader of

a chiefdom that covers large parts of Kasai-Central and extends into

Angola—accusing him of maintaining close ties to Tshisekedi’s Union for

Democracy and Social Progress. He was killed in August 2016 during a skirmish

with security forces, and in November, his followers launched an insurgency

named Kamwina Nsapu in response. They rallied supporters to rid Kasai of all

central government representatives and institutions, a call once championed by

their slain leader. They carried out both individual and coordinated attacks on

police stations, army installations, and local offices of the Independent

Electoral Commission (CENI).

Like other armed groups in the DRC, Kamwina Nsapu fighters

undertake spiritual rituals and oaths to forge cohesion and discourage

defections. With no identifiable leader, their demands are unclear, but the

rebels have cunningly exploited public grievances about the current political

crisis to curry loyalty. In February 2017, several fighters announced that the

implementation of the Catholic Church-brokered agreement between the opposition

and government was a core demand. However, they then extended their attacks to

Catholic churches and institutions. They also torched 600 schools and forcibly

recruited hundreds of children as human shields. The deadliest single episode

of violence occurred in late March 2017 when Kamwina Nsapu rebels ambushed a

police convoy and decapitated as many as 40 police officers. By mid-May, the insurgency

had spread to Kasai’s neighboring provinces: Kasai-Oriental, Lomami, and

Tanganyika. The government established a new military zone in these areas, but

its poorly paid, led, and trained soldiers have been accused of using

disproportionate force. In addition, the government brought in the rival Bana

Mura ethnic militia, to augment the government’s counterinsurgency efforts. The

Bana Mura, in turn, have been accused of “destroying entire villages, burning,

shooting, and hacking to death villagers, among them babies and young

children.” According to Catholic Church records more than 3,000 civilians have

been killed in Kasai since the insurgency erupted. The UN has reported 38 mass

graves and widespread violence against civilians.

Bana Mura fighters have directed their attacks mainly against

the Lulua-Luba community, which they accuse of supporting the Kamwina Nsapu.

The Bana Mura has also committed gruesome atrocities against civilians

perceived to be sympathetic to the central government, adding to the cauldron

of sectarian violence. Reacting to the deteriorating situation, UN High

Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein called the Kasai region “a

landscape of horror.” The government’s use of militias in Kasai and other

hotspots as a means of extending its reach contributes to this cycle of

violence. At the same time, this tactic undermines the security sector’s

legitimacy and the respect for the rule of law. Likewise, the support provided

to the rebels by some local politicians and businesspeople exemplifies the

region’s wider discontent with the central government.

Katanga

The lack of trust between Kinshasa and remote regions is a key

driver of conflict in Katanga in southern DRC, another major opposition

stronghold. It is the DRC’s richest province, accounting for 71 percent of the

country’s revenue and 95 percent of its exports. Shortly after independence,

Katanga was the seat of a vigorous, but ultimately unsuccessful, secessionist

campaign and was later a key battleground in the revolt that overthrew Mobutu

Sese Seko. The insurgents who unseated Mobutu were led by Laurent Kabila, the

Katangan father of the current president. After Joseph Kabila took the reins of

government, the region became a key regime stronghold and conduit for patronage.

This all changed in 2015 when, in the midst of a slump in mineral exports,

ex-Kabila loyalists from the area began to speak out against the President’s

maneuvers to derail elections. The government reacted by suddenly implementing

découpage—a policy that had long been in place but never implemented—to

increase the number of provinces from 11 to 26. Katanga was split into four

provinces, a rushed and ill-planned move that Katangan elites saw as a divide

and rule strategy. Découpage achieved the opposite of what Kabila had intended.

Rather than dismantling the opposition, it intensified Katanga’s swing away

from Kinshasa. As grievances have spread, so too have fears that the violence

that wracked this region in previous years might return. One of the armed

groups most likely to exploit the simmering tensions is Mai Mai Kata Katanga

(“Cut out Katanga”). It has overt links to Katangan identity issues, in

particular the deep sense of alienation from the central administration, and it

is linked to smaller secessionist groups, including Mai Mai Gideon (named for

Gideon Kyungu, who also commands Mai Mai Kata Katanga) and Corak Kata Katanga

(“Co-ordination for a Referendum on Self-Determination for Katanga”).

Mai Mai Kata Katanga gained prominence in 2013 when its fighters

stormed Katanga’s capital, Lubumbashi, and held it for several hours before

surrendering at a UN base. That same year, the UN reported that violence

between Mai Mai Kata Katanga and government forces spread to half of Katanga’s

22 territories and displaced a half million citizens. At the height of the

fighting toward the end of 2013 the group’s fighters were concentrated in the

northern parts of Katanga known as the “Triangle of Death,” where many still

remain, even though the violence has since died down. Others are clustered

around Sakania, on the Zambian border. While Katanga secessionists claim they

are fighting to defend the region against exploitation by Kinshasa, UN

investigators found that some of them are actually linked to prominent politicians

aligned with the government. As is the case in Kasai, the government uses

militias in its campaign against armed opponents.

Eastern DRC

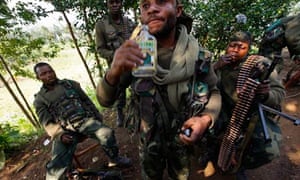

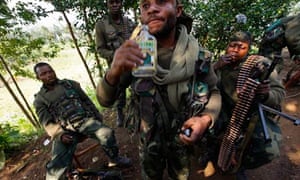

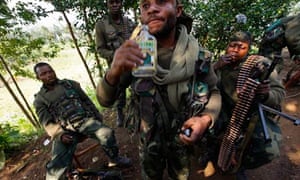

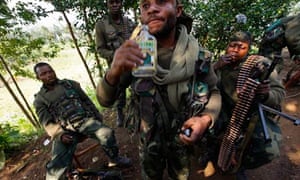

Congo’s two major wars (1996–1997 and 1998–2003) began in the

east. The region is home to the vast majority of the country’s 70 armed groups,

all pursuing shifting local and national agendas. Most of them are small,

numbering less than 200 fighters, but the havoc they have caused over decades,

especially in North and South Kivu, have made eastern DRC the epicenter of deadly

violence and humanitarian crises. The Kivus, which cover 67,000 square

kilometers and border Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda, are also a hotbed

of anti-government sentiment and activism (North Kivu alone is four times the

size of Belgium). The violence in this vast region stems from feelings of

marginalization from Kinshasa (over 1,500 km away) to grievances over the

allocation of local resources such as land, representation in the central

government, and the delivery of social services. These grievances also have

deep ethnic undertones that politicians and warlords manipulate to further

their interests. One example is the citizenship of the Banyamulenge (“people of

Mulenge”), which stoked some of the deadliest violence in the DRC. The Banyamulenge

were originally Tutsi cattle-breeders who migrated to the Congolese town of

Mulenge over a century ago. During periods of extreme unrest, Congolese

authorities questioned their citizenship and backed local militias against

them. The Banyamulenge and their local ethnic allies in turn launched several

insurgencies, one of which, supported by Rwanda, Uganda, and Burundi, engulfed

the entire country in crisis and led to the overthrow of the Mobutu government

in 1998. More recently, a series of failed attempts to integrate rebels into

the national army fueled a new wave of violence. It started out as a mutiny by

mainly Banyamulenge officers who previously fought against the government. This

group—the M23 (March 23 Movement)—took control of Goma, the capital of North

Kivu, in November 2012, and rapidly gained ground before finally being defeated

by the Congolese armed forces and the UN’s Force Intervention Brigade in

November 2013. Since that time, however, the M23 has begun to regroup and

reorganize, at times taking advantage of public anger at the central

government. In June 2016, fighting erupted in the south-central town of Kamina

when security forces attempted to prevent former M23 fighters from leaving a

camp for demobilized combatants. Concurrent to these clashes, thousands took to

the streets in nationwide protests against Kabila, including in Goma and the

South Kivu capital of Bukavu, another flashpoint of rebel activity. In July

2017, clashes broke out again in the two provincial capitals between demonstrators

and police. Protestors demanded that Kabila step aside and organize elections

according to the December 2016 agreement mediated by the Catholic Church.

Although there are no known links between political activists and rebels, the

surge in protests in these hotspots of deep anti-government sentiment created

an opening that could be exploited by armed groups like the M23 seeking to

reinvent themselves. Nina Wilén of the Université libre de Bruxelles explains,

“Even if the former M23 rebels do not seem to have any clear objective in

reforming their group, the fact that Kabila has outstayed his welcome can make

it easier for them to recruit new members in the Congo and legitimize their

existence.” The return of M23 could also fuel fresh sectarian violence and

cause more fragmentation in an already tense political environment. The

Tutsi-led movement is currently in direct conflict with local and regional Hutu

militias, the most powerful of which is the Democratic Forces for the

Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR). Numbering between 1,000 and 1,500, the FDLR was

created by former members of the Interahamwe and ex–Rwandan Armed Forces

responsible for the 1994 genocide against the Rwandan Tutsi. Its attacks cover

large parts of North and South Kivu. Moreover, the group has links to other

Hutu militias, and some local government officials. Both the M23 and FDLR have

been accused of widespread war crimes in the DRC, including massacres targeting

rival ethnic groups, mass rapes, and forced recruitment of children. Former M23

commander Jean Bosco Ntaganda is currently on trial at the International

Criminal Court for war crimes. The ICC has issued a warrant for FDLR commander

Sylvestre Mudacumura for similar charges.

Mai Mai Militias

A sizeable number of Congolese armed groups countrywide organize

themselves under the Mai Mai moniker, a term that signifies resistance against

outside agendas that are seen as hindering indigenous communities. But the

concept often takes on different political and cultural meanings depending on the

local and national contexts. During the Second Congo War, the local militias in

the east fighting incursions by Ugandan, Burundian, and Rwandan troops all

identified themselves as Mai Mai Congolese nationalists. While many Mai Mai

outfits retain this nationalist identity—mostly in opposition to immigrant

communities and ethnic Rwandans—the vast majority operate as local franchises

pursuing a mix of agendas ranging from the control of resources to extortion,

illegal taxation, and banditry. Some operate as religious cults, while others

function as private militias loyal to political and business interests. Still

others are focused on protecting their territories from rival Mai Mai. Some of

the larger Mai Mai outfits are explicitly political in outlook, and therefore

more likely to exploit the crisis between Kabila and his opponents to stoke

more violence. The Congolese Resistance Patriots (PARECO–Mai Mai) and the

Alliance for a Free and Sovereign Congo (Mai Mai APLS) both made—but ultimately

aborted—moves to become political parties. Similarly, Mai Mai Kifuafua

abandoned efforts to integrate into the military and returned to its positions

in North Kivu, where it has operated since 2009. Mai Mai Nyatura (“hit them

hard”) targets Tutsi communities in North Kivu in coordination with FDLR. In

response, Tutsi communities and their ethnic allies formed Raia Mutomboki

(“outraged citizens”) as a self-defense unit. By 2014, Raia Mutomboki had

morphed into an array of militias deployed across a swath of territory the size

of Belgium in North and South Kivu and parts of Ituri Province in the

northeast. Bunia, the capital of Ituri, saw some of the deadliest violence

during the Second Congo War, pitting the pastoralist Hema against Lendu

farmers. The European Union’s Operation Artemis, a peace enforcement force,

quelled the violence, leading to the disbandment of the Hema-dominated Union of

Congolese Patriots and Lendu-dominated Nationalist Integrationist Front. Both

groups subsequently joined the political process. However, the Lendu-dominated

Patriotic Resistance in Ituri rejected integration and remains active. Bunia is

now an epicenter of protests against the delayed presidential elections. In

January 2017, the Patriotic Resistance launched a series of attacks on CENI facilities

and stepped up recruitment in Bunia and surrounding areas.

Coming Apart at the Seams

Congo’s vicious cycle of political mismanagement, widespread

grievances, and sectarian violence is once again threatening to tear the

country apart. With no political deal in sight, the uncertainty is creating

conditions for the growth and expansion of new insurgencies and giving old

insurgencies a new lease of life.

Dormant for decades, the cultish secessionist movement Bundu Dia

Kongo resurfaced early in 2017. In May, it attacked the maximum security prison

in Kinshasa and freed 4,200 inmates, including hardcore felons and suspected

war criminals. It also freed its incarcerated leader and set parts of the

prison alight in what was the largest and most brazen prison break in the DRC’s

history. Like the Kamwina Nsapu, it combines mysticism with a populist and

potent anti-Kabila message. In September, a group of Mai Mai militias operating

under the banner of the National Peoples Coalition for the Sovereignty of the Congo

(CNPSC), also known as ‘l’Alliance de l’article 64’ (“AA.64,” in reference to

Article 64 of the Congolese constitution) captured Kigongo town in South Kivu

on the DRC-Burundi border. The offensive was a continuation of an uprising that

CNPSC launched symbolically on June 30—DRC’s Independence Day—to “liberate

Congo from a President who has lost legitimacy.” Some of these armed groups are

targeting their attacks on the electoral infrastructure—largely seen as an

expression of anger at Kabila’s unwillingness to implement the December 2016

political agreement. In South Kivu, armed groups, including Raia Mutomboki and

Nyatura, have attacked voter registration centers. In January 2017, Mai Mai

Gideon fighters attacked suspected FDLR sympathizers to prevent them from

registering to vote and also abducted CENI agents. Targeted violence against

voter registration has also occurred in Ituri, North Kivu, and Tanganyika. The

government’s use of militias to attack insurgents appears to be only creating

more chaos, while weakening government credibility. Consequently, strengthening

political legitimacy and adherence to the constitution will be a vital

foundation from which to try and regain support from across the periphery and

convince armed groups to lay down their arms.

No comments:

Post a Comment